When I started this blog last March, my intention was to write regularly about what it’s like to be a small book publisher, to pull back the curtain and expose how things really work around here. But within weeks of starting the blog, my dad was given a terminal diagnosis. The cancers — yes, plural — that he’d been staving off for years had finally made their move, and this wonderful human began his long goodbye.

So for much of the year, I was facing a book deadline for ParentShift in addition to the all-too-literal deadline for my dad. Meanwhile, the blog got shoved to, well, the margins of my life. The whole notion of writing what was “real” behind the scenes at BPP felt paralyzing. After all, what was real — what was dominating most of my thoughts — was that publishers have dads, too, and that sometimes those dads die. Yes, I could force myself to write about things going on around “the plant” (a vast overstatement, which is what makes it funny), but I’d be yada-yada’ing over the single most important thing.

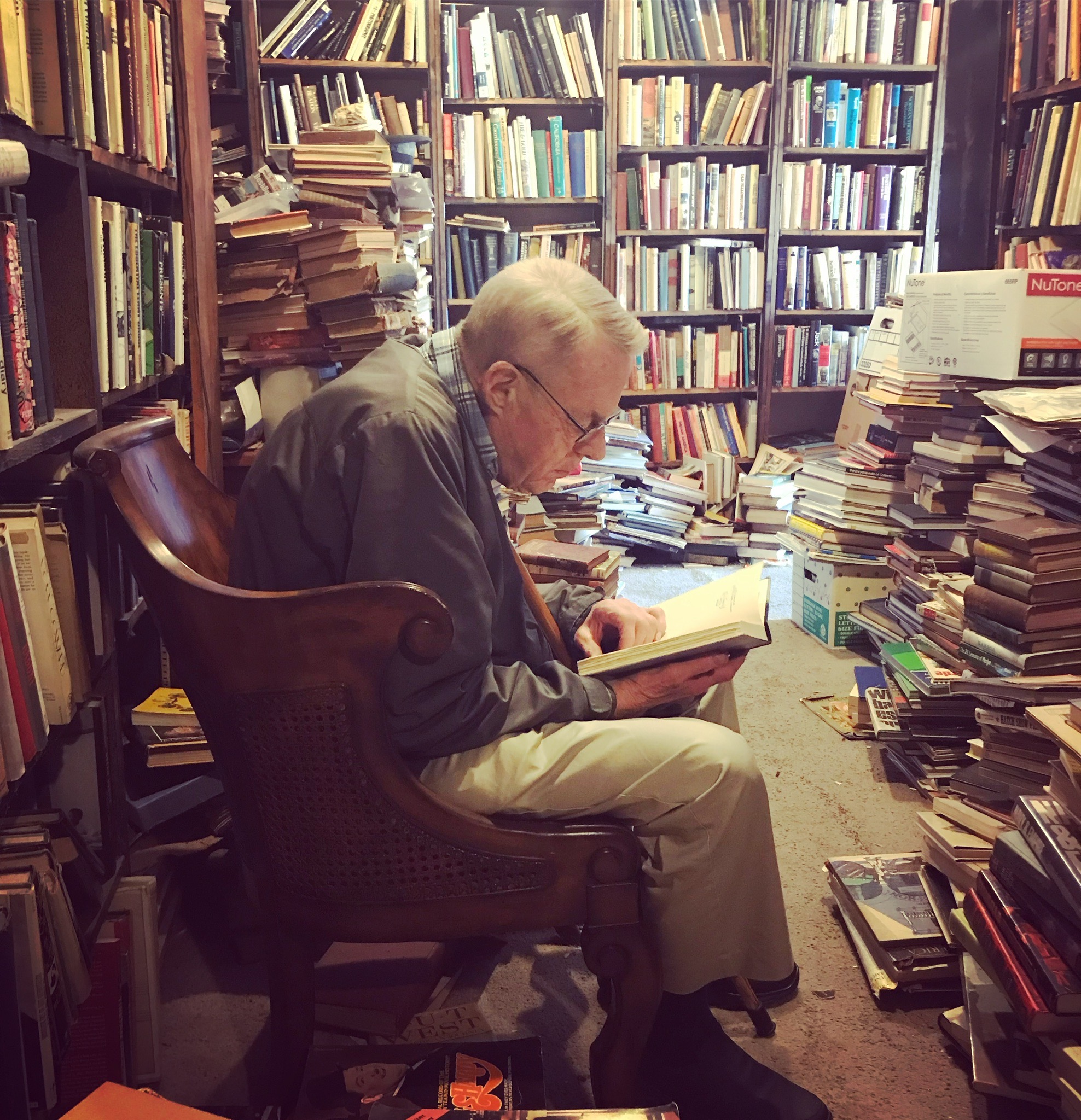

So here I am, dedicating this space, on this day, to that single most important thing — my father — a complicated man with a deep love of books (he never met a used bookstore he didn’t love), the quickest and wryest of wits, and the ability to find the funny in just about anything.

This is not an obit — if you want to read that, you can click here. This is more personal than that. It’s just something I need to do — because I loved him, because I miss him and because, in a very real sense, he’s the reason I do this work.

***

James Birch Thomas was born in 1939 in a tiny Missouri town called Mound City — population 1,200. Although his life’s journey took him, as a young child, to San Francisco, then later to Lincoln, Scarsdale, Brooklyn and Omaha, his road eventually curved back to Mound City — where I was raised for most of my life.

In Mound City, Dad was president of the Exchange Bank, a bank that had been built by my great-great-grandfather — a descendent of Robert the Bruce, Scotland’s “Outlaw King” — then handed down to my great-grandfather, then to my grandfather, and, finally, to my dad. A line of Thomas men who wore the Bruce tartan proudly every Christmas Eve.

Dad was a wise businessman and compassionate banker, but his real passion was never for numbers. It was for writing.

As a young father, shortly before his foray into banking, in fact, Dad pulled out his typewriter and spent a year finishing the novel he’d begun in college. He’d called the novel Beggar’s Shadows, taken from a line in Hamlet. The line is one of the play’s most profound, in my opinion — which is probably fitting, as I am quite sure Dad’s book offered a profound and lyrical look inside his own philosophical mind. I would love to have read it.

Unfortunately, I never got the chance.

After my dad finished his novel, he sent it out to a couple of publishers — both of which rejected it. Devastated, he burned the manuscript. It was his only copy.

I know, I know.

I suppose, in that period of his life, he felt he needed to be more “practical.” He had a wife and three children, after all. He had a family business awaiting him. But that one astounding, melodramatic, dream-ending decision burrowed itself into my psyche and stayed there.

As an author, I know the struggle well. I know the dread. I know the crippling insecurity and doubt and the desire to give up that comes with rejection. But I also know that rejection comes with the territory. Avoiding rejection as a writer is like avoiding water as a sea captain. No matter how well you steer your vessel, you’re going to get soaked from time to time.

I guess I wish that my dad would have known then what I know now: Being rejected by a publisher says absolutely nothing about the quality of one’s work, or the value, or the marketability. There are just too many subjective and constantly moving parts to make this process personal. It’s not a science. What gets picked is all about what that particular house needs at that particular moment in time. I wish that I could have been the editor who received Beggar’s Shadows. It would have been an honor to help make my dad’s dream come true. It’s why it’s such an honor now to do just that for others.

Dad encouraged my writing from the start, but never pushed one career over another. His own mother had been a reporter for the Toledo Times, and he had worked one summer, in early college, at the Laramie Daily Boomerang (real name!) in Wyoming. I suppose it stands to reason that I’d wind up in a newsroom, but he made me feel (and I believe it’s true) that he would have been just as happy if I’d become a crossing guard.

Still, during my early years in journalism, he read every story of mine he could get his hands on, commenting and asking questions. When I switched gears and started a blog, he never missed an opportunity to compliment my writing. And, when I started the press, he was always interested in knowing the ins and outs. Never did I post an update to Brown Paper Press’ Facebook page that he didn’t “like.” Often, he was the only one.

Dad read my first book, Relax, It’s Just God, many, many times. He edited early drafts; he offered needed insight and contributed important ideas. He never got a chance to read ParentShift, but we talked about it, and so many other things, during the last few years. That’s the thing about an extended illness; all time becomes quality time.

About a year ago, I asked Dad what his novel, Beggar’s Shadows, had been about.

“It was about people talking,” he said.

I could hear him, through the phone, taking a long drag on his Pall Mall cigarette — the one vice (besides Cheetos and donuts) that he refused to surrender in his old age.

“Those are my favorite kind of books!” I offered. “What was the plot?”

“There wasn’t one,” he quipped. “That was the problem.”

Dad was a consummate gentleman. He never missed an opportunity to hold open a door, pay a check, write a thank-you note, or come out to bid you a fond farewell when you left his house, waving goodbye as you pulled away.

I know he loved his family more than anything in the world, but he had a few other notable loves, too. They are, in no particular order:

Shakespeare;

Huckleberry Finn;

The civil rights movement;

Shane (both the book and movie);

Chess

Scrabble;

Golden Double Stuf Oreos;

Good conversation;

A well-crafted joke; and

Louis Armstrong.

My dad met Armstrong at a concert when he was 17, and listened to him almost exclusively throughout his life. Dad didn’t want a funeral, and he didn’t give a shit where we put his ashes, but he was clear on one thing: that we mark his passing by playing “When the Saints Go Marching In.” That man didn’t believe in much, but he sure as hell believed in Louis Armstrong.

One of Dad’s greatest loves, though, was storytelling. Dad collected anecdotes the way some people collect sea shells. He told his own stories; he told other people’s stories. And what he couldn’t remember, he made up. No, he may not have written his stories in books, but he certainly wrote them in our memories .

This is one of my very favorites (It just happens to be about me) .

When I was a kid, my parents took me and my friend Tommy to have dinner with the bank’s vice president and his wife. I knew the couple only as “Mr. and Mrs. Heck,” which I thought was downright scandalous at the time. In my day, “Heck” was considered a bad word.

On the way to dinner, in the backseat, I felt a need to brace my friend for this crazy-name situation.

“We’re going to dinner with friends of my parents, Tommy, and their names are Mr. and Mrs. Fuck.”

Trying to keep their composure from the front seats, my parents corrected loudly: '“HECK! HECK!” And then, through suppressed laughter: “Their names are Mr. and Mrs. HECK.”

My dad recounted this story many, many times over the years; it gave him no end of joy. The night before he died, weak and fading, he smoked his last cigarette and said the words that would be among the very last he ever spoke.

“Tommy,” he said, “their names are Mr. and Mrs. Fuck.”

Dad enjoyed a full life up until the very end. And when the end came, it came quickly. All of his children, and his beloved wife of 52 years, were by his side. We held his hand. We read him his favorite poem, “Stopping by the Woods on a Snowy Evening,” and we played ‘ol Satchmo on the Alexa.

“When you get to the other side, let me know if we were right,” I told him, squeezing his hand. It was just the sort of dark joke he would appreciate — and I like to think he heard it.

Like every good book, my dad wasn’t perfect. He had his flaws — some of which he could see clearly but never erase, others his eye just skimmed over, regardless of how many times they were pointed out to him. It’s why it’s so hard to edit our own work; as my mom once told me, so often we see what should be, rather than what is.

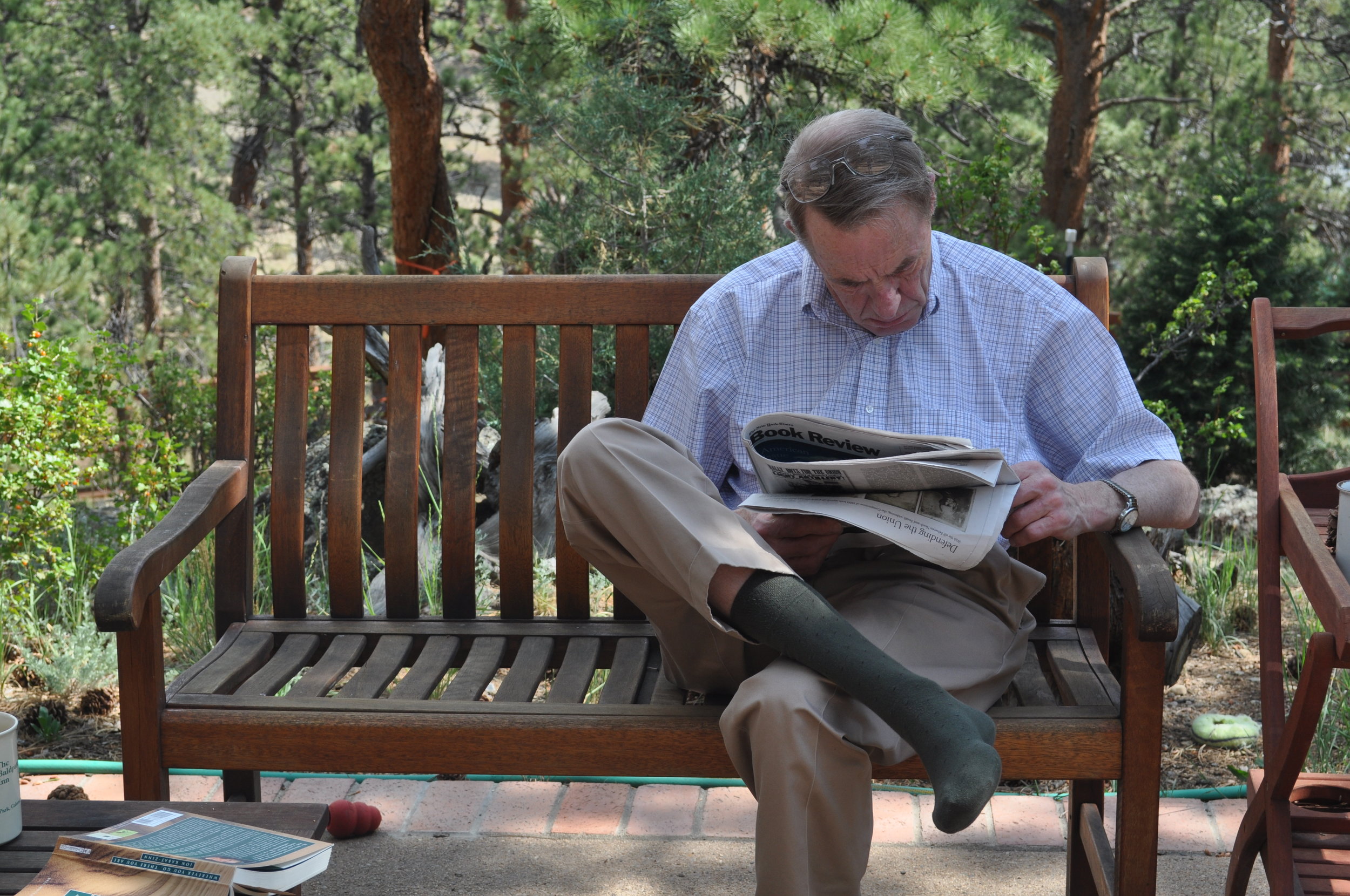

But Dad wasn’t impervious to change, either, and about seven years ago, he did a very brave thing. After retiring with my mom to Estes Park, Colorado, he decided to retire the Gibson martinis that had, over the years, become requisite to his evening plans. No AA — he was too skeptical for the higher-power part, I suspect — or treatment of any kind. Just a man who made a decision and stuck to it. It was an astonishing and powerful gift to his family, and to himself. He may well have been the first in that long line of Thomas bankers to banish the bottle. An Outlaw King in his own right.

There was a time I thought my own personal “iconic” image of my dad would be a picture I took of him in 1999, on the balcony of a hotel overlooking Bourbon Street in New Orleans. It was evening and he cut a slim figure, standing tall with a smile on his face and a Gibson in his glass. At the time, and for many years after, the image was classic Dad.

Now, though, looking back on his life, I am (secularly) blessed with so many iconic images of my sweet pop.

Dad with Satchmo.

Dad on his wedding day.

Dad walking me down the aisle.

Dad in his Christmas suit, Bruce tartan scarf and glittery, gold bow atop his head.

And the last — an image I must have seen dozens of times: Dad still cutting a slim figure, standing tall, with a smile on his face. Only this time the glass is missing, and he is waving goodbye.